The Notes in an Octave

Seven Notes (swara) & 12 Pitches (shruti)

In Hindustani (North Indian) classical music, an octave is called saptak and has seven notes called swara. These notes are sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni (similar to the Western do re mi fa so la ti).

The first and fifth notes (sa and pa) have only one variant. The other five notes (re, ga, ma, dha, and ni) have two variants each. The notes re, ga, dha, and ni have natural and flat variants, while ma has a natural and a sharp variant. All together, therefore, there are 12 distinct pitches (shruti) in an octave when variants are included.

The video below demonstrates the 12 notes in an octave using a keyboard, while showing the difference between the natural and flat/sharp variants of each note. In each case, the natural variant is sung first followed by the flat or sharp variant. I use C as my starting point (sa) and have color-coded the natural notes red, the flat notes pink, and the sharp note maroon.

Natural vs. flat/sharp variants of all the notes

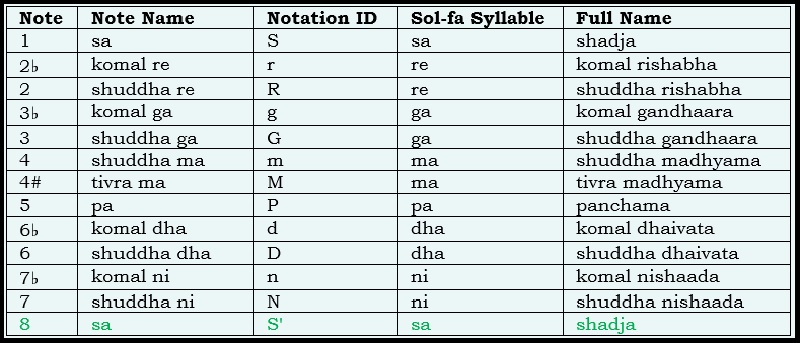

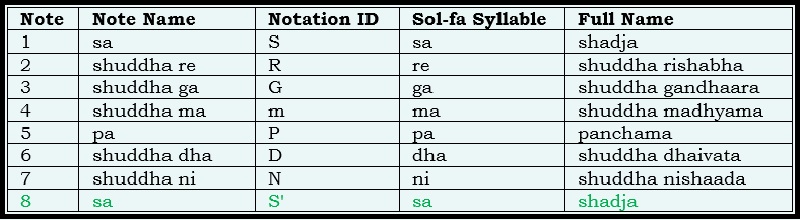

Table 1 below provides a summary of the notes in an octave. In the "Note Name" column, the adjectives shuddha (natural), komal (flat), and tivra (sharp) are used to specify the variant of the note being referred to. The notes sa and pa are not modified because they have only one variant each.

To notate the 12 pitches ("Notation ID" column), I use the first letter of the note name plus upper or lower case to denote the higher or lower pitched variants, respectively: S(1), r(♭2), R(2), g(♭3), G(3), m(4), M(#4), P(5), d(♭6), D(6), n(♭7), and N(7).

It is important to keep in mind that in Hindustani classical music, the notes have unique and unchangeable identities in relation to sa. So, unlike in Western music, where D♭ can also be C#, and E♭ can also be D#, etc., in Hindustani classical music, the pitch following S(1) is always r(♭2), never #1, and the pitch following R(2) is always g(♭3), never (#2), and so on.

Table 1. The notes in an octave in Hindustani music

The third column gives the Indian solfa syllables for the notes. Note that the same solfa syllable is used for both variants of a note, because they are simply considered to be variants of the same note. The full names of these seven notes (swara) are shadja, rishabha, gandhara, madhyama, panchama, dhaivata, and nishada.

We call solfa "sargam," an acronym created by combining the first four syllables (sa re ga ma). Singing in sargam is not just for voice training in Indian classical music – it is also used as part of musical performance, as one of the tools for improvisation.

In the performance below, Venkatesh Kumar sings in sargam between 9:10 to 11:15 or so.

Venkatesh Kumar

Raag Durga

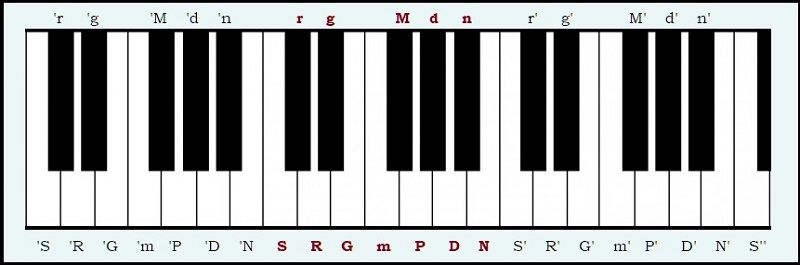

The final sa in Table 1 belongs to the next octave and is notated S', with a quotation mark after it. I notate notes in octaves below or above my main octave with quotation marks before or after them to show which octave they belong to. Here is an illustration using C as sa.

Entire keyboard notated using C as sa

Movable Do

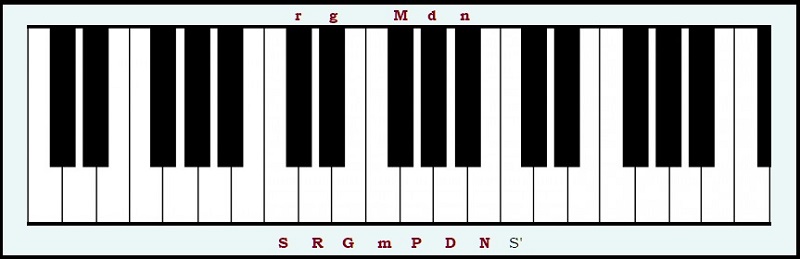

Indian classical music uses a movable octave, which means you can begin your octave at whatever pitch you like, and the other notes are defined in relation to your starting point (sa).

Octave notated using C as sa

Octave notated using B♭ as sa

Ten Parent Scales

So, there are a total of twelve pitches in an octave. But for creating music, you usually choose specific pitches from among those twelve pitches to give yourself a theme. Since melody is so central to Indian music, we are always on the lookout for pitch combinations (scales) that offer significant melodic potential. These are called ragas, and we know of about 500 ragas in the Indian classical tradition.

Ragas are classified in various ways. One system is to classify them under ten parent scales, known as "thaat." These are similar to modes in ancient Greek music. Unlike ragas, which are more flexible in the number of notes they can include, parent scales are always heptatonic and must include one each of the seven notes (swara) - sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha and ni. Variations arise due to the different variants (natural, flat, or sharp) used. The video below demonstrates the ten parent scales. Once again, C is the tonic (sa) and I have color-coded the natural notes red, the flat notes pink, and the sharp note maroon. For the sake of efficiency, the video has been set at a brisk pace, but feel free to adjust its speed by clicking the settings button.

The ten parent scales

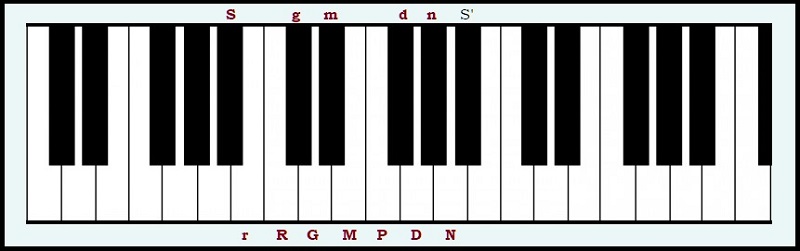

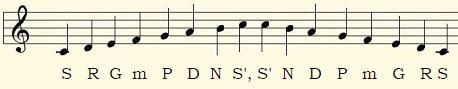

All new students of Hindustani classical music begin by learning the Bilawal scale comprising all the natural notes, S R G m P D N.

Table 2. The all-natural Bilawal scale

The Natural Origin of Notes

Musical notes correspond to certain frequencies (pitches) relative to the tonic (sa). These are frequencies at which the sound produced is clear and pleasing because it is consonant (i.e., in agreement) with the tonic. At other frequencies, the sound is dissonant (clashes with the tonic). The tonic is played constantly in the background in musical cultures that use a drone (or something like the tanpura in Indian music), but even when it is not physically played, it is present in our minds as we listen to music. The way our minds make sense of music is by being aware of the tonic and understanding the other notes in relation to it. Therefore, the pitches that are pleasing to hear are those that are consonant, and it is these pitches that are traditionally used for music by all cultures.

The video below has to do with vibrations, frequencies, and resonance. It will help you visualize what happens when you find a frequency that is consonant with the tonic, and why there are only some pitches that are pleasing while others are not.

The power of consonance

22 Shrutis

The word shruti literally means "that which is perceived by the ear," and in the context of music, it means a unique pitch that can be distinguished from other pitches. For an elementary or intermediate-level understanding of Indian classical music, it is sufficient to understand that there are 7 swaras and 12 shrutis in an octave. However, many ancient Indian texts on music, going back all the way to the Vedas (Chandogya Upanishad, 6-8th century BCE), talk about an octave being divided into 22 shrutis. Understanding this involves delving deeper into the physics and mathematics behind musical notes and their frequencies relative to the tonic. I have written about this in detail on a different forum, and will provide the link here for those who are interested.

What is the logic behind dividing an octave into 22 notes?