The long journey of Indian classical music can be traced back to two notes in the Vedas – the higher note (udātta) and the lower note (anudātta), separated by a whole tone.

Melody and rhythm are as old as humanity, and there is no reason to believe that ancient Indians were familiar with only two notes. What udātta and anudātta represent are the earliest notes that were scientifically identified and standardized for consistent replication and transmission.

Vedic Respect for Scientific Rigor

The Vedas are ancient Hindu scriptures. There are four Vedas, and each one is a large collection of hymns. These hymns are so highly revered that an enormous effort has been dedicated to their precise oral transmission from one generation to the next, altering not even a single syllable or its intonation. Vedic schools across the Indian subcontinent have maintained this unbroken tradition for thousands of years.

Some centuries ago, when European scholars came across the Vedas and began to study and document them, they were surprised to find that Vedic schools in distant corners of India, geographically far removed from each other, had preserved identical versions of the Vedas.

Remember that this was an era when, leave alone the Internet, there wasn’t even a well-developed postal system. This made it unlikely that Vedic schools in far flung regions of the subcontinent would have regularly communicated with each other or compared notes. They had simply preserved identical versions of the Vedas independently of each other.

This was made possible by the rigorous oral transmission techniques developed to ensure precise transmission of the Vedas over millennia, combined with the faithful implementation of these techniques to this day. Historians estimate that the Vedas have remained unaltered for at least the past 3000-3500 years.

It is in light of this respect for scientific rigor in the preservation and transmission of ancient texts that we must understand the development of musical notes in the Vedas.

Evolution of the Seven-Note Scale

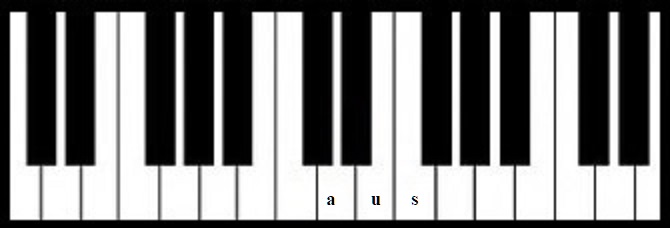

Following udātta and anudātta, a third note, svarita, was introduced. It was positioned a semitone above udātta. These three notes – udātta, anudātta, and svarita – are still the only ones used in the Rig Veda, the oldest Veda.

It is the Sāma Veda that is credited with identifying and documenting all seven notes of the musical scale. Derived from the Rig Veda, the Sāma Veda adapts select hymns from the Rig Veda into musical form.

While the Rig Veda has 10,600 verses, the Sāma Veda has only 1,875, but it is considered the longest Veda due to its detailed musical notation of each hymn in addition to the hymn itself.

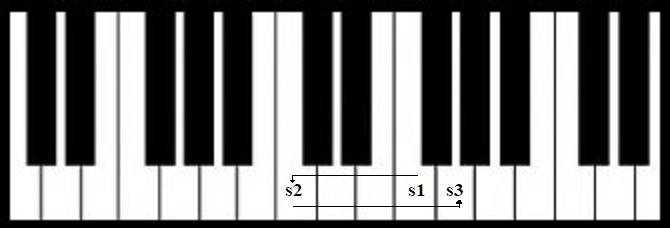

Initially, Sāma Veda chants used three notes, like the Rig Veda. However, Sāma Veda chanting involved multiple sets of priests – e.g., prastotā (initiators), udgātā (lead singers), and pratihartā (responders) – who sang different parts of a hymn from different tonal centers.

These tonal centers were typically a fourth or fifth apart from each other as these pitch intervals are easily derived and replicated.

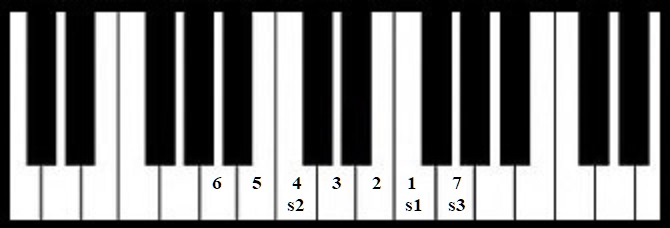

This use of multiple tonal centers expanded the original three notes (udātta, anudātta, svarita) into a full seven-note octave.

Three-note chants with s1 as the tonal center use notes 1, 2, and 3. Chants with s2 as tonal center use notes 4, 5, and 6. Chants with s3 as tonal center use notes 7, 7♭, and 2, but the Sāma Veda does not mention flat notes, so we will focus on notes 1 through 7 for now.

Religious, Classical, and Folk Music in Ancient India

Vedic music was not music for entertainment. It was integral to religious rites and ceremonies, and was performed strictly as prescribed, without alterations.

However, over time, the music theory developed through the Vedas was applied in secular contexts, giving rise to Indian classical music. This music, rooted in the path (“mārga”) established by sages, became known as “mārgī.”

Mārgī music was rule-based, highly structured, and standardized across the Indian subcontinent, with minimal regional variation. It was typically performed by trained musicians in formal settings such as royal courts, temples, theaters, and scholarly assemblies. Mārgī music was based on “jāti,” the precursor to “rāga” in Indian classical music.

Meanwhile, folk music, known as “deshī,” was “sung with delight and freely of their own desire in their respective regions by women, children, cowherds, and kings alike” (from the 6th century text Brihaddeshi by Matanga).

Deshī music was vibrant, with complex rhythms, intricate ornamentation, and strong emotional appeal. However, it lacked a standardized structure or rules, leading to significant regional variation across the subcontinent.

Evolution of Rāga from Jāti

Vedic texts[1] primarily discuss Vedic (“vaidika”) music, but also mention secular (“laukika”) music in passing.

In the post-Vedic period, major texts such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata (mid 1st millennium BCE) describe the music of their times, especially mārgī music as performed by trained musicians.

The Natyashastra by Bharata (c. 2nd century BCE – 2nd century CE) is a comprehensive treatise on the performing arts, with several chapters on music. These chapters detail the notes and pitches in an octave (svara, shruti), tuning systems (grāma), scale modulation (murchhanā), scales as used in performance (jāti), ornamentation (tāna), rhythms (tāla), and other core musical concepts.

Remarkably, none of the above texts makes a significant effort to explain rāga.

It is only in the 6th century or thereabouts that we finally encounter a clear description of rāga, in the Brihaddeshi. This marks an important milestone in the evolution of Indian classical music as we know it today.

Rāga evolved from jāti. Jāti are essentially scales, but with additional attributes, such as starting notes, dominant notes, weak notes, resting notes, and so on. This is exactly how we define a rāga even today – by its ascending and descending scales, dominant notes, weak notes, resting notes, and so on. So, how are the two concepts different?

The main difference is that jāti emerged from music theory, while rāga evolved more organically, influenced by living folk traditions. Rāgas evolved as a result of mārgī musicians drawing inspiration from regional folk music, creating new scales or enriching jāti-based music with folk ornamentation and rhythms.

The names of the two concepts reflect this difference beautifully. The word jāti means “type” or “category” (similar to “mode”), whereas the word “rāga” is derived from “ranga” (color). As the Sanskrit saying goes, “ranjayati iti rāgah” (that which colors the mind is a rāga).

Essentially, a rāga is a jāti brought to life with color and passion through the fusion of mārgī and deshī music. The strong theoretical foundation and rigor of mārgī music merged with the rich variety and emotional appeal of deshī music to elevate and enrich both traditions.

Indian classical music as we know it today is a direct offshoot of Vedic musical scholarship, but infused with the richness of living folk traditions from across the Indian subcontinent.

What could be a more beautiful legacy to inherit?

Suggested further reading

The songs of our ancestors — Vedic music from 1500~ B.C.

The Vedic Roots of Rhythm in Indian Classical Music

[1]Texts from the Vedic period (pre 500 BCE) or texts attached to the Vedas, such as Naradiya Shiksha, Chandogya Upanishad, and Panchavimsha Brahmana.

Leave a Reply